If you’ve ever wondered why your Linux system asks for a password or why you can’t access certain files, you’re dealing with Linux Users and group management—whether you realize it or not. Today, I’m going to break down everything you need to know about managing users and groups in Linux, and trust me, it’s not as complicated as it might seem at first.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Linux treats everything as a multi-user environment, even if you’re the only person using your laptop. This might seem like overkill, but it’s actually brilliant for security. Every file, every process, and every service runs under a specific user account. This separation means that if one part of your system gets compromised, the damage stays contained.

I learned this the hard way when I first started with Linux. I ran everything as root (the superuser) because it was “easier”—until I accidentally deleted half my system with a mistyped command. That’s when I truly understood why user management isn’t just bureaucracy; it’s self-preservation.

How ServerAvatar Makes User Management Easier

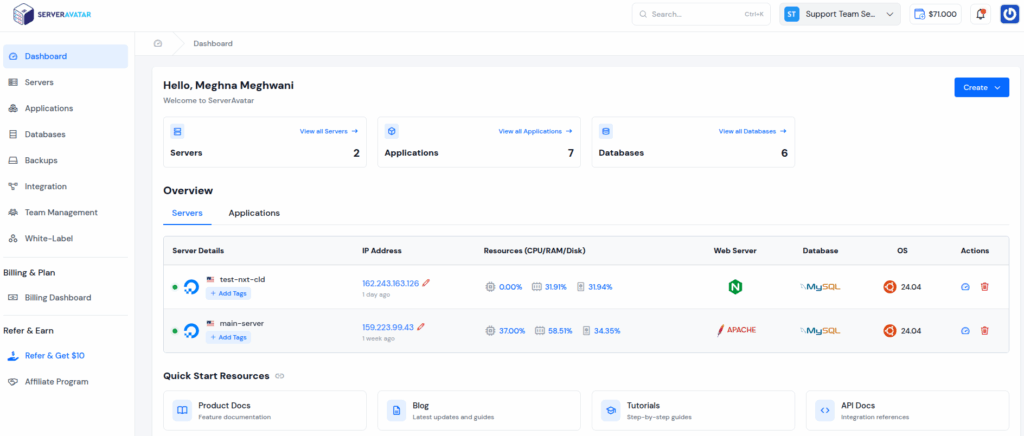

Managing users on a VPS or cloud server can quickly become complicated, especially when hosting multiple applications. ServerAvatar makes this process effortless by automating user management while prioritizing security. As a modern server and application management platform, it streamlines deployment and ongoing management with minimal manual effort.

One of ServerAvatar’s standout features is application user isolation, which assigns each hosted application its own dedicated Linux user. This isolation ensures that if one application is compromised, it cannot affect others, keeping your server environment secure and stable.

Key Features of ServerAvatar’s User Management:

- Application User Isolation: Each application runs under its own dedicated user, preventing cross-application access.

- Enhanced Security: Limits the impact of a compromised app by containing threats within that app alone.

- Automated User Management: Reduces manual work by handling user permissions and configurations automatically.

- Isolated Environment: Ensures apps cannot access each other’s files or processes, blocking unauthorized interactions.

- Protection Against Attacks: Contains threats like malicious scripts or rogue plugins to a single application, preventing wider damage.

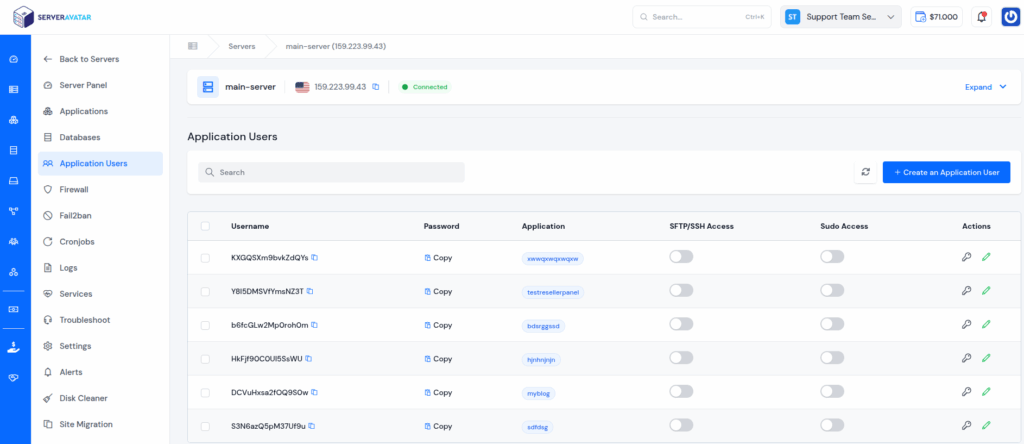

Isolation Environment in ServerAvatar

You can host multiple applications on a VPS or cloud server easily with ServerAvatar’s isolated environment. It creates a dedicated Linux system user for each application so that one app cannot touch the files or processes of another.

Whether it’s a compromised script trying to reach sensitive files via absolute paths or a rogue plugin running PHP code from WordPress, isolation ensures these attacks are contained to that specific app.

Creating Your First Linux User

Let’s dive into the practical stuff. The most basic way to create a user is with the useradd command, though I’ll be honest—it’s a bit bare-bones:

sudo useradd johnThis creates a user called “john,” but here’s the catch: no password, no home directory (on some systems), basically just a name in the system. Not very useful, right?

Here’s what I actually use when setting up a new user:

sudo useradd -m -s /bin/bash -c "John Smith" john

Let me decode this: -m creates a home directory (you definitely want this), -s /bin/bash gives them a proper shell to work with, and -c “John Smith” adds their real name as a comment. Much better.

Don’t forget to set a password:

sudo passwd johnNow, if you’re using Ubuntu or Debian, you’ve got a friendlier option called adduser:

sudo adduser sarahThis beauty walks you through everything interactively. It asks for the password, full name, phone number—the works. Sometimes the simple tools are the best tools.

Modifying Users

Real life is messy, and user accounts need to adapt. Maybe John needs access to Docker, or Sarah’s getting married and wants her username updated. The usermod command handles all of this.

Adding John to the docker group without messing up his other groups:

sudo usermod -aG docker johnThat -a flag? Absolutely crucial. Forget it, and you’ll accidentally remove John from all his other groups. I’ve seen this mistake cause panic more times than I can count.

Need to temporarily disable an account? Maybe someone’s on vacation or under review:

sudo usermod -L john # Lock the account

sudo usermod -U john # Unlock when readyChanging someone’s home directory (happens more than you’d think):

sudo usermod -d /new/home/path -m johnGroups: Because Teamwork Makes the Dream Work

Groups are how Linux handles shared permissions efficiently. Instead of giving five developers individual access to a project folder, you create a “developers” group and manage them collectively.

Creating a group is refreshingly simple:

sudo groupadd developersAdding users to this group:

sudo usermod -aG developers john

sudo gpasswd -a sarah developers # Another way to do itHere’s something that trips people up: users need to log out and back in for group changes to take effect. Can’t tell you how many times I’ve troubleshot “permission denied” errors only to realize the user just needed to refresh their session.

Removing someone from a group:

sudo gpasswd -d john developersDetective Work: Finding User and Group Info

Sometimes you need to investigate who has access to what. These commands are your magnifying glass:

id john # Everything about john's account

whoami # Who am I logged in as?

groups sarah # What groups is sarah in?For deeper investigation:

cat /etc/passwd # List all users (don't worry, no actual passwords here)

cat /etc/group # See all groups

getent group developers # Who's in the developers group?

last # Who's been logging in recently?That last command has helped me spot unusual activity more than once. If you see logins at weird hours or from unexpected locations, it’s time to investigate.

Cleaning House: Removing Users and Groups

When someone leaves the team, you’ll need to remove their access. You have a choice to make:

sudo userdel john # Removes user, keeps their files

sudo userdel -r john # Nuclear option - removes everythingI usually go with the first option and manually archive their home directory. You never know when you’ll need that old project file they were working on.

For groups:

sudo groupdel developersJust make sure no one has this as their primary group first, or you’ll get an error.

Real-World Best Practices

After years of managing Linux systems, here’s what I’ve learned:

Document everything. Future you will thank present you when you’re trying to remember why the “webapp” user has access to the backup directory.

Use descriptive usernames. “john_smith” beats “jsmith1” when you have three J. Smiths in your organization.

Regular audits are your friend. Set a calendar reminder to review user accounts quarterly. You’d be surprised how many ex-employees still have active accounts in some companies.

Never share user accounts. If two people need access, create two accounts. When something breaks, you’ll want to know exactly who did what.

Test permission changes on a non-critical account first. There’s nothing worse than locking yourself out of your own system. Yes, I’ve done it. No, I don’t want to talk about it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the difference between useradd and adduser?

Think of useradd as the manual transmission and adduser as the automatic. useradd is the low-level utility available everywhere but requires more options. adduser is a friendlier Perl script in Debian/Ubuntu that holds your hand through the process.

Can I change my own username in Linux?

Not while you’re logged in as that user! You’ll need to log in as a different user with sudo privileges, or boot into recovery mode. It’s like trying to paint the floor you’re standing on.

How many groups can a user belong to?

Typically, a user can belong to up to 32 supplementary groups on most Linux systems, plus their primary group. If you’re hitting this limit, you might want to reconsider your group strategy.

What’s the difference between primary and supplementary groups?

Every user has one primary group (assigned when the account is created) and can have multiple supplementary groups. When you create a file, it’s owned by your primary group by default. Supplementary groups give you additional permissions.

Is it safe to edit /etc/passwd and /etc/group directly?

Please don’t! Use the proper commands like usermod and groupmod. Direct editing can break your system if you make a typo. If you absolutely must, use vipw and vigr which at least check for syntax errors.

What happens to a user’s running processes when I delete their account?

The processes keep running! This can be a security issue. Always check for running processes with ps -u username before deleting an account, and kill them if necessary.

Can I have spaces in usernames?

Technically no. Usernames should start with a letter and contain only letters, numbers, underscores, and dashes. Stick to this rule and save yourself headaches.

How do I see when a user last changed their password?

Run chage -l username. This shows password aging information, including the last change date. It’s great for enforcing password policies.

Conclusion

Managing users and groups in Linux isn’t just a technical chore, it’s one of the most important steps in keeping your system secure, stable, and organized. By controlling who can access what, you create a safer environment for both your data and applications.

While traditional Linux commands give you full control, platforms like ServerAvatar take it a step further by automating these tasks and ensuring strong security isolation for every application you host. Whether you’re running a single WordPress site or managing multiple projects on a VPS, ServerAvatar keeps everything clean, separate, and protected, without the headache of manual user management.

So, the next time you set up a new server or deploy an app, remember: effective user and group management isn’t just good practice, it’s your first line of defense. And with ServerAvatar, that defense comes built right in.

Stop Wasting Time on Servers. Start Building Instead.

You didn’t start your project to babysit servers. Let ServerAvatar handle deployment, monitoring, and backups — so you can focus on growth.

Deploy WordPress, Laravel, N8N, and more in minutes. No DevOps required. No command line. No stress.

Trusted by 10,000+ developers and growing.